Return Value Optimization

01 May 2015Motivation

After about a year and a half of coding in C++, things are finally starting to click. Learning the syntax is just the tip of the iceburg, what’s more important is the underlying behavior and possible side effects of our choices. For example, what happens if you don’t make an accessor of a member function const? Usually, nothing - but as time goes on, and more engineers modify the same component, the chance of introducing a side effect, or using the accessor incorrectly goes up. Making the member function const is a signal to the compiler to tell you better how you screwed up. And it’ll continue to do that for the future contributors to the project. The latent benefits and optimizations of the compiler are worth exploring and understanding.

What is RVO?

One such optimization is called Return Value Optimization. As wikipedia states, RVO is when an extra parameter is passed into the function to be populated with the return value instead of being populated in the return value register. This parameter is a pointer to the variable being assigned the output of the function. This can be used to save an extra copy via assignment, as well as simplifying the code and consequently, more readable. This optimization is done by the compiler when it realizes that the return value of the function is being assigned directly to a newly declared variable.

Let’s say you want to write a range function in C++ which populates a std::vector with a range of integers. A simple range function might have a min and max argument, with the assertion that max must be greater than min. Since we are returning a container that can dynamically grow and shrink, thus makes use of heap memory and executes a deep copy within a copy constructor or assignment operator, we’d want to avoid copies

// Assertion max > min

static void range(std::vector<int>& v, int min, int max);

// Usage

int main()

{

std::vector<int> v;

range(v,10,20);

std::cout<<v.size();

// Output should be 10

}The ‘wrong’ way to do this would be return it by value (which in theory instantiates a deep copy), and have the callee assign the return value to another vector, either by assignment or copy constructor, thereby instantiating a second deep copy.

// Assertion max > min

static std::vector<int> range(int min, int max);

// Usage

int main()

{

std::vector<int> v = range(10,20);

std::cout<<v.size();

// Output should be 10

}With return value optimization, which is supported by any modern C++ compiler, the two range functions are equivalent. In the underlying assembly code, no copy operations of the vector are occuring, making it both efficient and in my opinion, easier to read.

Measurements

But how do we prove to ourselves that this is actually doing what I say it does? There are a couple of ways: 1) to peruse the generated assembly of both functions and deduce their equivalency, 2) to run it through strace and view how many system calls to malloc are being made, or 3) benchmark it to procure empirical results and plot it. I went with option 3.

I originally tried reading through the generated assembly to no avail. The majority of the code was standard library code bloat, making it a nuisance to parse through. Then I tried running both implementations through a variety of range sizes, and comparing it to a range implementation that executes a deep cop on the return value on purpose, to simulate what the RVO implementation would do by design.

#include <vector>

#include <iostream>

#include <assert.h>

std::vector<int> rvo-range(int min, int max)

{

std::vector<int> result;

assert(max > min);

while (min < max)

{

result.push_back(min++);

}

return result;

}

void standard-range(std::vector<int>& result,int min, int max)

{

assert(max > min);

while (min < max)

{

result.push_back(min++);

}

}

void without-rvo-range(std::vector<int>& result,int min, int max)

{

std::vector<int> temp;

assert(max > min);

while (min < max)

{

temp.push_back(min++);

}

result = temp;

}Results

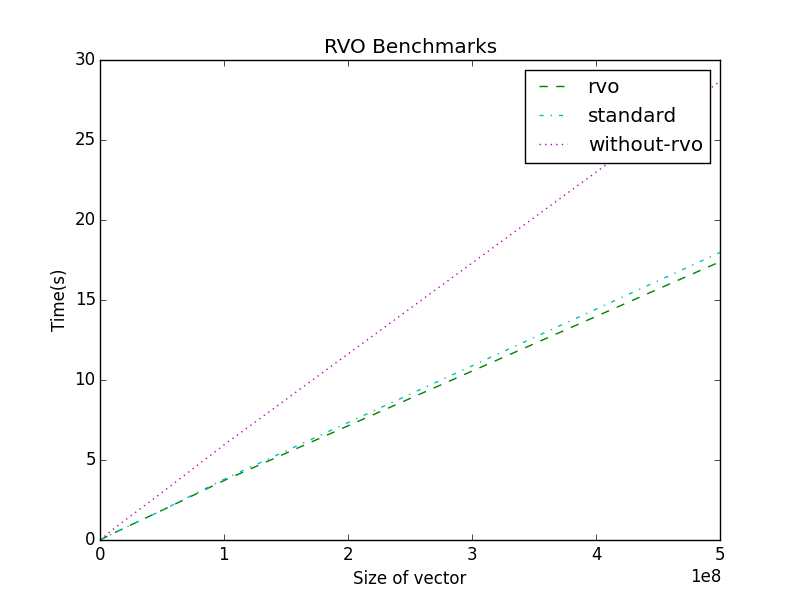

The x axis describes the size of the vector being create by each range function, and the y axis represents the real time to accomplish this task. The unix time command was used to measure duration, and matplotlib was used to plot this data. As you can see, the rvo and standard implementations are relatively equivalent, on my machine (Retina Macbook Pro), the rvo implementation was actually slightly faster over several runs. The implementation that simulates what would have happened if rvo didn’t exist (without-rvo) is about 50 % slower, with just an extra copy operation.

Additional literature

If this interested you, I’d suggest reading more about Copy Elision and how it can help you.

If you liked this, my next post is about Unordered Maps vs Vectors with a focus on compound keys.